“Are you ready to win it all?”

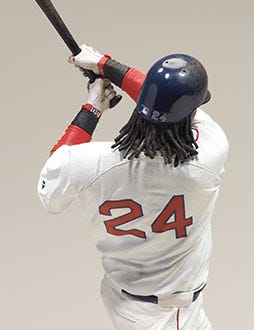

It was early 2004 when Manny Ramirez asked my uncle, Michael, the question. The Dominican sensation with the indominable stroke had visited Mike in a dream, just ahead of our family trek to spring training.

How could we have known that the Red Sox would, that year, defy a generational curse and deliver us to the holy land of a World Series championship? We didn’t, not really—but Michael was certain his visitation had been a premonition of some kind. Telling we relatives about the REM-time interaction, the die-hard Sox fan was excited, confident, unburdened. Who wouldn’t want to win it all? But, at that point, only Mike could concretely parse the message’s meaning. Yes, he had told Manny. He was ready. And so, he did.

Michael Patrick McGuirk, born Saturday, January 31, 1970, passed away Thursday, July 18, 2024, at the age of 54. A genius of a historian, writer, musician, cook, uhh… gamer I dunno you get the picture—he was a man of many talents, a sizable group of close friends, and a boundless amount of love, both coming and going. He was a creature of compassion, wit, and intelligence—a devourer of life.

As he tells in his brilliant degenerate grift of a memoir (sorry I’m bad at impersonations) Strike Four, not long after he had that vision, he was diagnosed with an incurable disease, a hereditary degenerative disorder that depletes the ability to control one’s muscle movement, which he lived with for 20 years. Shit, I’m spoiling the book. While the same illness that undid the lives of his mother and sister, spinocerebellar ataxia type-1, pulled at his threads, he committed himself to living the fullest life available, which was majestically amplified through the company and never-ending support of his beloved friends.

Faced with this impossible situation, he found his way with courage and grace, forgoing resentment more than humanly reasonable, doing everything he could to be as little of a burden as possible to his loved ones (except for needing money), living for the pleasures of life, even as he was being progressively robbed of them, and being generous to those he knew could fall prey to struggling with missing him, even when he was right in front of them.

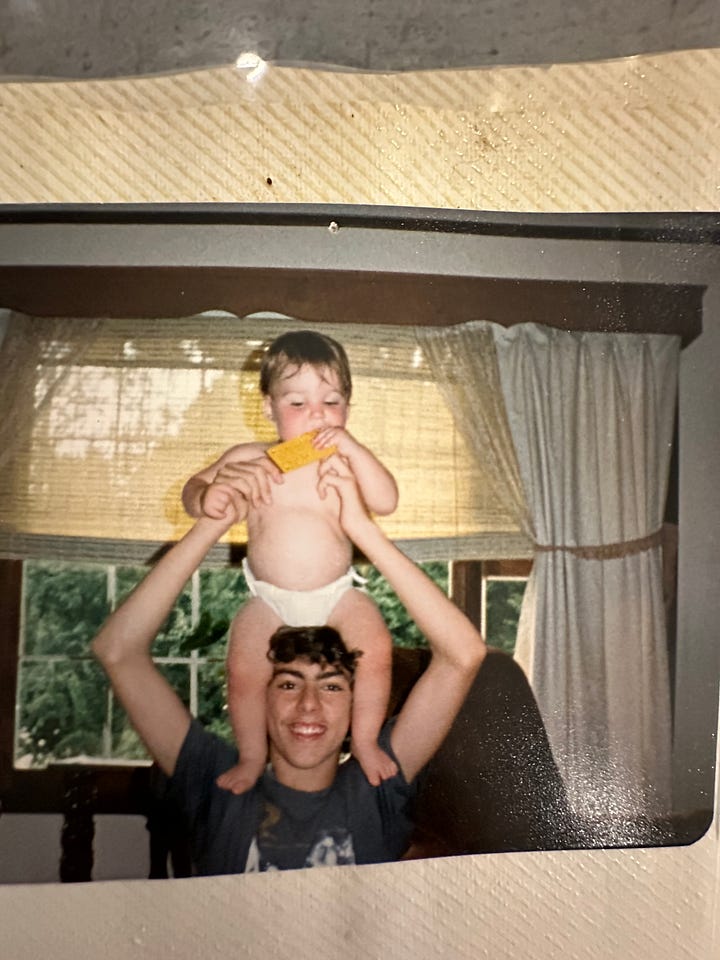

Mike’s my dad’s little brother, and when I was a little thing he was something like a halfway adult to me. Only 14 years my senior, he’s responsible for many of my first memories of play. You don’t forget the first time your uncle shows you how to blow up a Matchbox car with firecrackers, for example, or when he and his best-friend-of-a-cousin break out the family’s newfangled video camera to make you and your baby sister the stars of a macabre film about vampires preying on youth—complete with ketchup gore special effects. You don’t forget the priceless hand-me-downs, like a trove of vintage MAD Magazines, or Peanuts and Life is Hell digests, or a pint-sized guitar.

You never forget any of that.

I’m struggling to draw a tidy circumference around the man’s influence on me, expansive as it was. He was a living monument to the idea that life can be lived however you conceive it. Perhaps above all, he was treasured—a cult figure in his own right, a best friend to many, a favorite person of all who knew him. Mike was impossible not to love. Which was lucky, considering the brief prayer of a motto he got inked across his back: “I NEED LOVE.”

On Repeat

That 2004 baseball trip was a fateful one. Together with my aunt, dad, sister, and cousins, we piled into a van and drove across central Florida to watch Boston’s boys of summer tune up over the spring. In a fateful twist, we had only one volume of music to enjoy together as we made the drive—ABBA Gold, a collection of the Swedish act’s greatest hits. When preparing for the trek, Michael had pulled together an assortment of CDs to soundtrack the ride, but in our rush to get out the door he’d forgotten all but the one. Accordingly, we listened to the tunes over and over, much as we could tolerate and a little more. It became both a running joke and a torture device.

But then shit got really weird.

We’d made it to southern Florida for our next game and went to get dinner. We found a nice restaurant and were seated in the rear patio, near the boardwalk. There was a TV playing music videos. And, wouldn’t you know, the second we sat down, an ABBA song played on the screen. And another. And another. It was a marathon. It didn’t end. We started cracking up at the apparent cosmic practical joke. It made no sense. But there was something in the air that night…

Mementos

I feel guilty remembering my uncle through the stuff he gave me, but it’s not entirely my fault—he’s the one with the impeccable sense of taste and timing. I was probably in fourth grade when, for my birthday, he delivered a gift of immeasurable coolness—the Millenium Falcon, fresh in its newly reissued box. My dad had introduced my sister and me to the franchise in a lavishly theatrical fashion not long prior, which made this feel like I was being given a car—a Cadillac, even. It had to have been the most extravagant toy I’d ever received. While it was just some plastic thing, the message it conveyed was unmistakable: Here, kid. I loved this thing when I was your age—and I’m sure you will, too. Have a friggin’ blast.

Now, I’m not sure Mike would’ve found my toy collecting as an adult quite as rock-n-roll as I myself might hope, but there had been a hidden backstory to the Falcon gift. Michael had gotten one for Christmas way back in the day, I guess, and my dad had gone to great pains to hang the smuggler’s ship with fishing wire so it was suspended aloft when Mike saw it that December 25 morning. So, in a way, his gift to me was a repayment of a family debt. No wonder he was so psyched about it.

My debt to Michael would only mount from there. When I was about 12, and my sister Ali was 8, he decided we’d start a band. The Youngins only played one gig, at Kirkland Kitchen in Cambridge, and we only really knew one song, Deep Purple’s Smoke on the Water. I played guitar and Ali played drums. I was very limited, and couldn’t even properly play the chords. But those rehearsals in his cramped industrial closet on the far side of Central Square were the most fun I ever had practicing something. He was incredibly patient, I remember, and confident that we’d pick it up. He invested in us, and both Ali and I could sense the meaning of that.

I proved a little too insecure in my abilities to front a band, but Ali found herself in it. The Youngins show kicked off what would become a lifetime of live music performance for her, taking her all across the globe as she’s grown as a songwriter, performer, and artist. And I’d learn to scratch my stagetime itch via karaoke. But it all started with us repeatedly incanting, “Smoke on the water… Fire in the sky.” Just over and over.

I’ve been rifling through my stuff for all the shit that’s got a connection to him. Mike always knew just the gift for the occasion, like the engraved watch he gave me for my confirmation, or the pairs of dollar store nunchucks he gave each member of our family one Christmas. Casually hilarious, he made being equal parts thoughtful and irreverent look easy.

Know It All

When it came to music, Mike knew everything. And to be in his orbit was to reap the benefits.

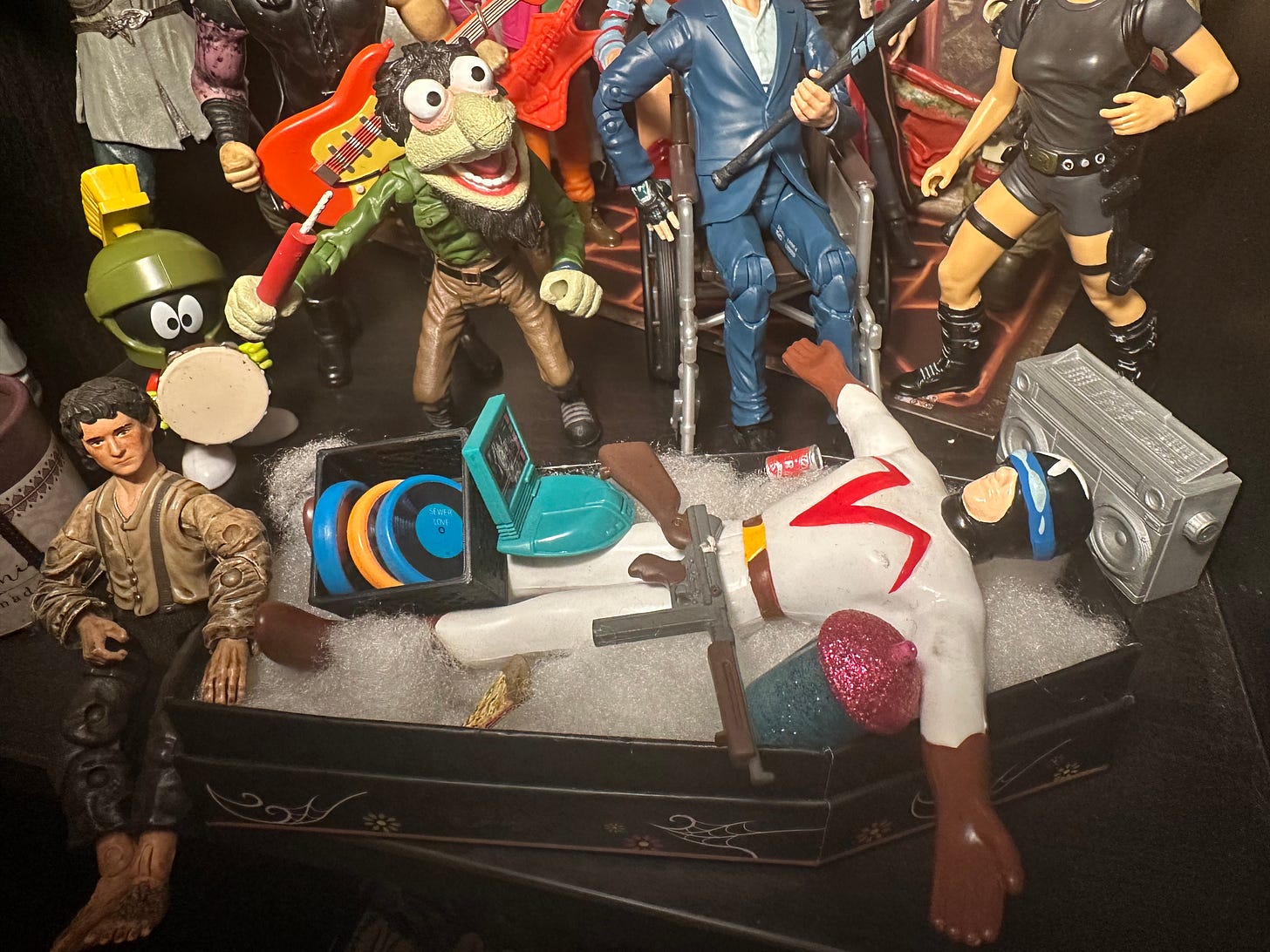

When I was in middle school, going on my first solo-trip, flying out to see my grandmother in the sunshine state, he gave me a mixtape that would become one of my life’s most prized media artifacts. Titled Goin’ Down Flo’da Way, he made it a codex of everything I’d need to know about music. It had Pavement, Nirvana, the Ramones, and the Electric Mayhem along with Pink Floyd, John Lee Hooker, and Eric B. & Rakim. The 90-minute sonic odyssey was sequenced in a way to be fun and digestible for me, a gentle lecture that I’m still catching up with to this day. I can only regret that the mixtape did not launch me into exploring the millions of horizons it might have, though it did give me a lifetime appreciation of a thoughtfully curated mix and sparked a few new loves for me.

Notable among them was the Paid in Full - Seven Minutes of Madness remix, which introduced me to hip-hop on terms I could meaningfully connect with—it not only had its commanding narrative verse, but the song was punctuated by silly and provocative samples that filled out the canvas and made a collage of it. It was a dazzling way to make acquaintances with what was emerging as the corner of music most vital to my generation, and years later when I found myself writing about hip-hop professionally, I was always well served to have familiarity with the formative classics. Thinking of a master plan indeed.

Then there was David Gilmour’s There’s No Way Out of Here, a nightmare of eternal loneliness. That one haunted me. So did Don’t Play Cards with Satan, Daniel Johnston’s manic battle against the possessing demons in his midst. I don’t mean to overstate it, but every song on the tape popped with novelty and oozed meaning. I never stopped cherishing it—the mix was the first thing I played when I heard Mike was gone. What a gift.

That music-wired brain made Mike a natural fit at a new Somerville store, Record Hog, in the late 90s, where as I recall he was to function as a sort of librarian, selling shit on occasion. Him amid those tens of thousands of records, as opposed to his usual personal collection of thousands, left a lasting impression. Think “pig in shit.”

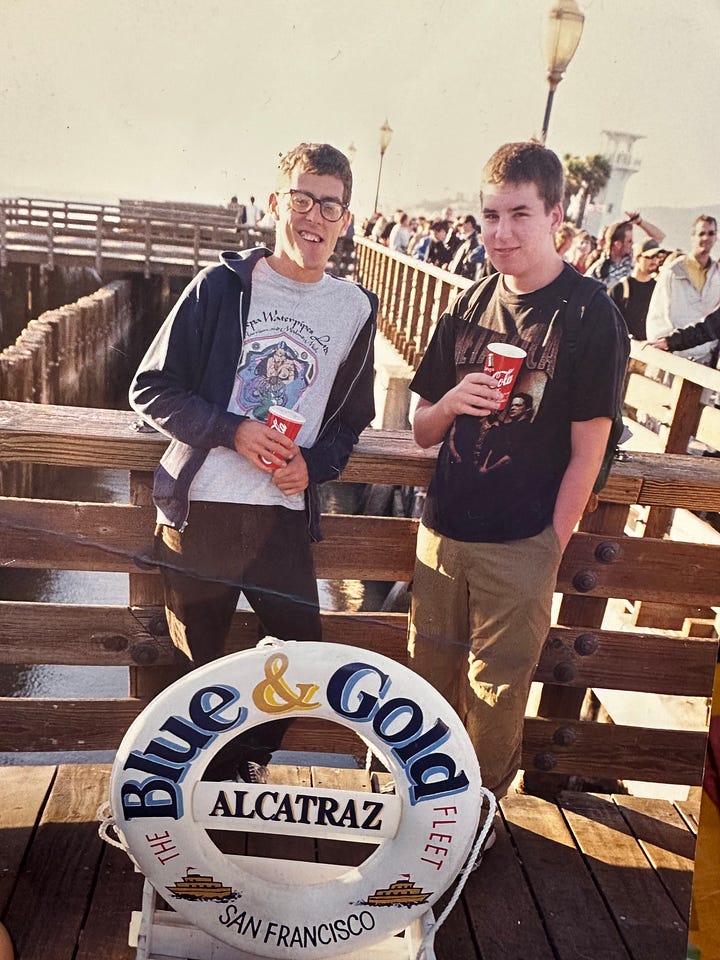

That place stands out to me because one of my least favorite memories from growing up came not long after he got that gig, when I learned that Mike would be moving out west to San Francisco. After making music for a while, including with the groups MUNKY and Pudding Maker, and having as I understood it some partying ups and downs, I think he felt he’d plateaued around his hometown, and so he decided to follow a girl he liked out west. That subsequent distance would always be hard for me to accept, but what made it easier to come to grips with was the fact that Mike was clearly never fully home until he was in SF. He got a prime gig working for one of the precursors to today’s streaming music giants, where he helped catalog all kinds of music, notably midcentury soul and gospel albums. It was there that he helped pioneer a kind of pre-Tweet microreview journalism through which he would find his writer’s voice, the one that won him no small amount of acclaim—including being prominently featured in Da Capo’s Best Music Writing 2006.

I find it difficult to fully eulogize my uncle here, and go through his entire biography, because my prism of knowing him is through that of being his nephew, not his peer. From that vantage, though, I’ll just say; he was fucking cool, man. He organized the world’s coolest baseball league, where misfits and reformed jocks made horny jokes on the same diamond. He became a notable music writer in his town, reporting in detail for the San Francisco Bay Guardian on the scenes and microscenes and pan-flashes and legacy acts and everything that drew his interest for even a moment. I’d be remiss not to include mention of his decision following his diagnosis to move to Thailand, years spent living as the farang with the heart of gold, who was buoyed by locals who saw his tortured tourist soul and smiled. Again, read Strike Four.

Before that, later in 2004, after the dream but before the ring, I spent the summer crashing with him at his place in the Mission District. At 19, my sophomore year in college behind me, I was overwhelmed by how cool he and his world were—everyone seemed to be a dirty kind of sexy, unconventional and uninhibited. Trucker hats were big at the time, or had just gone mainstream. I was too young to get into most bars or gigs, but we had a good time nonetheless.

One night, Mike was supposed to sneak me into someplace to see a friend’s band, but the wrong doorman was working, so I was shit out of luck. I decided to go to the movies, where after taking in the durable Ben Stiller vehicle Dodgeball I weaseled my way into an opening night screening of Spider-Man 2. I left thinking it was the greatest movie I’d ever seen, because I was and am that way, but the night had grown late and the buses had stopped running. These were the days before cell phones rose to ubiquity, so short on options I figured I’d just make my way back to the apartment on foot.

It was a long walk, like a couple hours maybe. I was proud to know the way. It made me feel like a local, and it was a quiet way to see the streets of San Francisco and its, uh, y’know, colorful nightwalking denizens. By the time I got home, Michael was freaked. “Where you been, kid?” But he wasn’t pissed—just worried. He, of anyone, knew that sometimes shit like that just happens.

Another fun memory from that summer came on my last night, before my return flight to Boston. After going hitless in countless at-bats in his league, we went out to the batting cages to see if I could get my shit together. I bat lefty but probably shouldn’t, because while the swing feels more natural I never make contact, whereas I feel weak from the right side but can make decent connection at a better rate. Which is a long way of saying, when I do bad at baseball, it comes as no surprise. That night at the cages I thought I was finally catching the groove when I squared up and made solid contact, only for the ball to skip down the bat and pop me right on the thumb. I went down in a heap, my hand on fire. I’d later learn the thumb was broken, fractured right at the base of the nail. At that point that night, though, all I was thinking of was making my flight the next day undisturbed.

We returned to Mike’s apartment and he offered me the best painkiller he had at his disposal: whiskey and Budweisers. He played records, probably Stones and Pink Floyd or something too obscure for me to place, and we hung out and got moderately wasted. It hurt, but drinking the pain away probably befit the end to that summer, which marked the first time the two of us indulged together. My time out there came and concluded a little bit too soon. Had I gone back there a few years later, when I’d grown more into my skin, I wonder what sort of shit we’d have gotten into. But then, that’s a silly thought—that would be impossible. Because he was about to get his diagnosis. In fact, I think he was starting to get suspicious about it when I was there, though he kept a tough front.

Now, Mike might have partied a little, but it was largely hard to hold it against him. It was fun to listen to him play music for hours and split a 30-rack of the King of Beers. It reminds me of what he said about his #1 co-addictions, Coca-Cola and Doritos: “This shit will kill you… but it tastes so good.” I know, it’s a simple sentiment, but Mike lived like there was no tomorrow even before he got sick. In fact, he’s said to have lost all his baby teeth early because he was so hooked on Nesquick strawberry milk. His teeth would go on to be a recurring issue but one that got better with the help of supportive loved ones—lucky guy, to have people that love you enough to protect your smile.

Pen15 Club

My uncle Mike was a great writer, and a huge influence on my ambitions in that arena. It all started with a brief inscription left in his first book, a comprehensive review of music festivals across the planet. On the opening pages of my copy, he wrote, “Dear Brendan, This book sucks—don’t read it. Just remember, I wrote it and you didn’t. Love, Mike P.S. Neither did your father.”

There’s not a day where that dedication can’t make me laugh. He said all I needed to know—in opposite speak. Don’t admire this work, don’t engage with it. But be challenged by it. Think of someone you know bringing a tome to life. I took it as motivation. He was just fucking with me, no doubt, but I took it as gospel.

I think a lot of Mike’s writing was like this—stylish, specific, brief, in total command of his audience, wry but not cynical, an absolute maestro. When he started to keep his blog, I was in heaven. Reading felt like sitting next to him as he tells you the world’s funniest story. He was brave in his work, taking risks that you as the reader won’t bail on him and his crazed persona and fringe lifestyle. It was like he knew that his audience loved him, so he was able to be a little freer than he might have otherwise. When he published his big book, Strike Four, in 2016, it felt like it was made in gold—Mike’s voice, undisturbed by ataxia, in the palm of your hands.

The book was a huge accomplishment, one made possible by his friends and community and celebrated accordingly. Not crashing that release party is just one of those regrets that’ll stick with me. Because that community is a rare one, stepping up in the biggest of ways to help him over the progressive years. My family and I owe an incalculable debt to them, for loving my uncle the way that they did—through real care.

Through the help of those friends, Mike was able to keep writing as the years went on, sharing hilarious vignettes from his life as well as brief ruminations on music. Check it out, and you’ll see that on the page, in his words, he’s as alive as ever.

The Hard Part

Ataxia robbed us all of more time with Mike. I wish it didn’t get harder but it did. It was a dance he knew was coming, having been a loyal and unwavering helper to his mother, Jeannie, and sister, Dee Dee, as the ataxia did its number on them. It starts with loss of balance, but with simple tools that can be remedied easily enough. What follows is a loss of autonomy, but the right help can smooth and ease that transition, and you can negotiate a world that works for you—or, at least, Mike could. Then, though, goes the language, as the act of speaking becomes a labor and a frustration, but even this can be mitigated by familiarity with both the speaker and the disease and its verbal impacts. Still, it’s a one-way train of loss. “This shit ain’t easy,” I can hear my uncle telling me, as I aimed to be half the helper he was to our family. “But we are in this together.”

Losing Mike is hard, and it’s been hard, even though he’s given us plenty to remember him by. From favorite records to hundreds of pages of his written thought, to favorite memories. In all of them, I think, his voice—his real voice—carries.

One night when Mike’s voice rang out that I’ll be holding onto came about 12 years ago, when he was visiting Boston and we went out. I’d become something of a karaoke freak and was eager to show him my scene. He was totally game, down for a night with my friends. We ended up at the Hong Kong in Harvard Square, successfully navigating the stairs to reach the second-floor party. Who knows what I sang—something like Kanye West probably, anything to try and impress Mike, convince him of what I thought was cool. I wish I had crystal clear memories of that night, because we had a blast, but the only thing I know for sure is the song Michael sang: Blue Bayou by Linda Ronstadt.

I was surprised by the choice. I thought he’d go with more of a hard rock classic. But Mike’s love of music and genres couldn’t be pigeonholed. He was seated as he sang, clutching the microphone with both of his increasingly scrawny hands. Singing could not have been easy with his condition but he did so ably, sweetly, and even movingly, warbling in falsetto, crooning in earnest.

After, he’d tell me he chose the cut because he knew I’d remember it— Ronstadt sings it beautifully on our beloved Muppet Show. He gave me a gift when he sang that song, a keepsake. I wonder how often he was doing that, knowingly or otherwise—offering a loved one a memento of himself, crafting a memory to be shared as time ravaged on, giving gifts to last.

The night he died, I went out to meet up with friends, and I sang Blue Bayou for him. Then I did the Stones’ Let It Bleed, because singing his favorite band felt right. And we all need someone we can lean on.

I’ve always wished I believed in mysticism. I could use the peace. Still, as I sang for my uncle that night, welling up, I felt connected to something. I felt that night he sang it was just within arms’ reach. That, like the song says, I could go back someday to Blue Bayou, and be somewhere carefree, unspoiled by the ills of the world, together. And maybe that will only ever exist in the music, in the song. But Michael made sure I knew which one to play to find him. What a gift.

Be Not Afraid

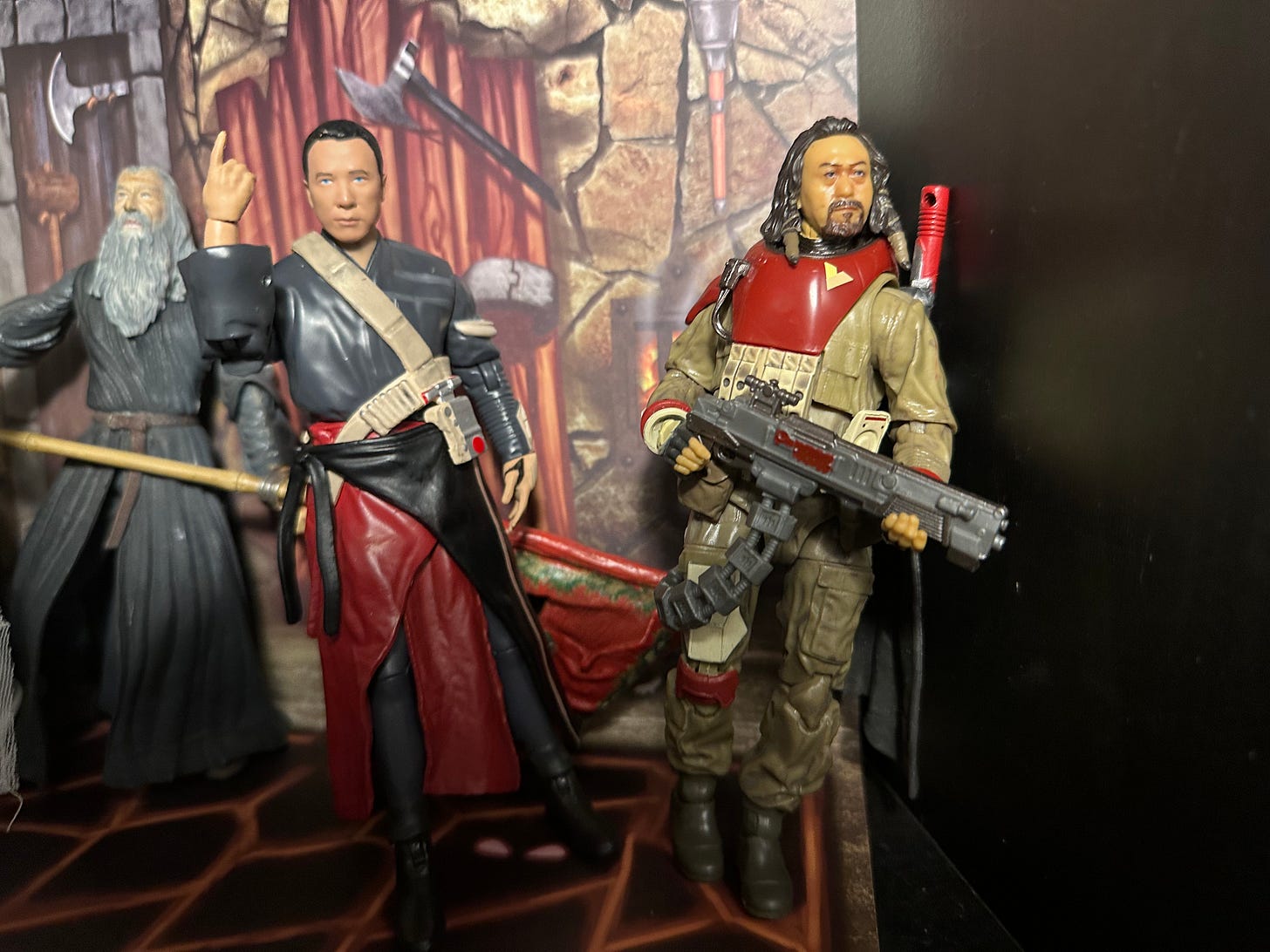

I wish I could remember every record he played me. I wish I could remember every movie he said I needed to see—I know I’m supposed to watch Bridge over the River Kwai with his dad, and there were a bunch of Herzog ones. Herzog came up after he cameoed in the Star Wars streaming show we binge-watched over a visit a few years back, when I was in the midst of a mental health crisis and Mike was reaching a wall in terms of being capable of living without 24-hour care.

It was my first big trip since Covid, and I’d missed my uncle something fierce. Mortality was never more present than those years of constant fear of airborne illness and especially given my state I was desperate to be sure I didn’t miss my chance to see Michael, particularly in his home element. We had a great week of Marlboro Reds, Doritos, Cokes and Buds, and again, a shitload of Star Wars. We watched some Ralph Bakshi cartoons, too. It was wholesome, in its way. I’d live in the memory of that week if I could.

One night Mike decided he wanted an Italian feast. Food was always big for Michael—he could cook an unforgettable meal, as he did a few family holidays, and as he was robbed of agency left and right the taste and texture of things was something he could savor. With his swallowing issues, he knew some foods were dicier than others, but food was a risk he wanted to take. Eager to keep him happy, I ordered us the huge meal requested.

While the food was on its way, I got a weird feeling. I decided I’d need to look up an instructional video on how to administer the Heimlich maneuver, just in case. It was an uncharacteristic bit of preparedness. I was insecure about my concerns, and didn’t want my sense of precaution to bum him out, but Mike totally got it. It was a straightforward, 90-second lesson, and I felt much better for having watched it. Now, we could eat.

The first thing Mike requested was the fried calamari, a favorite dish of his mother’s. I fed the breaded seabeast to my uncle. Only, there was a problem. He quickly gave me the two-hands-to-the-throat “choking” signal. I sprung to action, picking his skinny body up from out his chair and working the process to expel the deadly seafood. Never had I been enveloped by fear like this. It didn’t take long, we were successful in dislodging the offending morsel. But the upheaval left us both on the floor, rocked by adrenaline. “That was terrifying,” he confessed. “I think… I think I’m that scared all the time,” I responded, only realizing the truth of what I’d said as I heard myself say it.

Eventually, he wanted the calamari again. Who was I to say no?

The Winner Takes It All

I’m frustrated. This was supposed to be funnier, a literary romp through memories of my uncle, where you get to know his characteristics and qualities through the stories I’m able to summon. But I fear I have just told you a few dry anecdotes about myself in which he’s an indescript costar. I wanted to tell you about the tattoo across his back and why it feels like a sacred family motto, or the AK-47 inked onto his forearm solely out of his love for Grand Theft Auto. I want to impart to you how funny he was, how cherished he was by his friends and family, how wise and fearless he was in prosecuting his life, before and after its climactic revelation. I wanted to give you the why, not the what. And I wanted to keep my Uncle Mike alive, I guess—but my words can only incant so much.

So, perhaps we should add some of his. The following is excerpted from Mike’s Strike Four chapter on his visit from Manny Ramirez.

When I woke up, I didn't think much of it at first. I was like, “I had a dream and Manny was in it.” Then I remembered. Manny POINTED at me and said, “Are you ready to win it all?” That's a message from God. Or at least Manny Ramirez. No, but it couldn't be about the Red Sox winning—that was never gonna happen—“Are you ready to win it all” meant that you can have everything in life, you can have more than you ever dreamed—everything—but you have to allow yourself to have it. And that is something you need to learn, to be ready for.

There's a lot there. Life is a gift if we make it a gift. No. Ugh. That sounds awful. The thing is, we CAN have a life that is a gift—we can have it all—if we don't let the bad shit in our brains fool us into thinking we don't deserve it. I'm not talking about The Secret, or some such “I’m entitled to a yacht!” BS. I mean happiness, and joy, but also hard stuff—“it all.” The challenge has two parts. One is the fact that we make our lives. Sure, there are things that happen that are random but it's the decisions we make that put us wherever we end up. That's a lot of responsibility. The other thing is that life may have some shitty things in it, but that is part of the gift that it is.

Jesus, that sounds a whole lot better four beers in. Less preachy. Less pie-in-the-sky-y. But I wanted to write this whole thing out so I could figure out how it'd work as a chapter in the book or something. We're both learning here. The thing is, “Are you ready to win it all?” totally became my motto after this. That morning I called like 10 people to tell them about it. I really did start thinking in this way, and still do. We make our lives.

Two weeks after the dream, I had gotten laid (a rarity, no lie); in October, the Red Sox went on their unbelievable run; and a year after that I somehow found myself floating in a massive pool in Thailand, shooting pool and playing Grand Theft Auto pretty much all the time. Talk about joy. I also got diagnosed with this disease that summer (2004). That's the “all” part. You can't have it all without bad stuff.

I guess you can’t have love without loss, either. There’s no life without time, no memories without finitude.

The whole tenor reminds me of something Michael said to me a few times during our last visit, over the winter. Remembering his own Uncle Mike, who passed last summer, he summoned his namesake elder’s words of skeptic longing, which I’ll paraphrase.

To believe in God is to be ignorant. But not to is to be arrogant.

I don’t know. I told you about me and mystic stuff. But I’ll tell you that the last gift I gave Michael was a special request—a miniaturized statuette of The Pieta. Why he’d be comforted looking at the suffering Michelangelo depicts, I can only wonder. But I have to imagine it has to do with mystery, with inspiration, with pain acting as a ballast to the everyday gift of life—particularly given the closing passage of his book’s epilogue.

I say fuck all religions for all time and forever. The Thing—whatever IT is—whatever it is that made math, all this hatred, all this judgment didn’t come from it. WE made religion. I don’t know. I don’t know anything, really. All I know for sure is that this thing loves us. This thing loves us so much that if we were exposed to it, our brains would melt. I know this. I also know that the last word in this book will be pussy.

Hilarious vulgarity aside, here rests a man who believed in the conquering power of love. He believed in the beauty of man-made things. He strove to bear as few resentments as he could, he found magic in music and art, he kept good company and made for even better. He was, through it all, indominable. He was my hero.

So I guess that begs the question—am I ready to win it all? I’m still fumbling with that one. I’d like to think so. I’m still batting back the demons, of course—the doubt and despair and inadequacy. But reflecting on the wholeness of my life with my uncle, I’m coming around on the idea that life is a gift, an everyday miracle, and that there are little glimmers of magic dust in the margins.

After all, I, too, have seen curses felled by mortal men.

This really makes me wish I'd met Michael because I feel poorer for having missed his company. And not to damn you with faint praise, but reading these little excerpts of his writing-- his voice sounds a lot like yours.

Also, as I am writing this, literally a moment ago, I just saw you bike by and waved. Another small synchronicity, the kind that seemed to reveal themselves to Michael all the time.

Thank you for that!